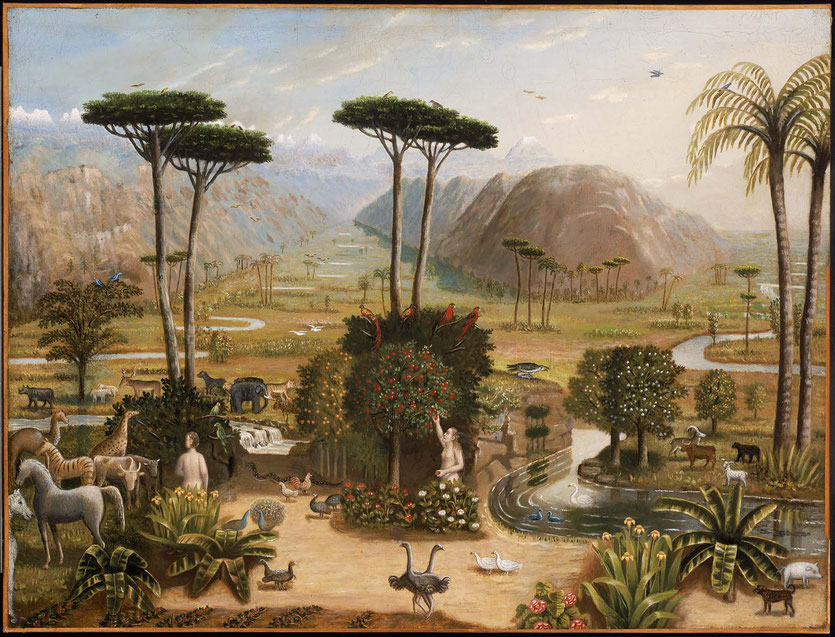

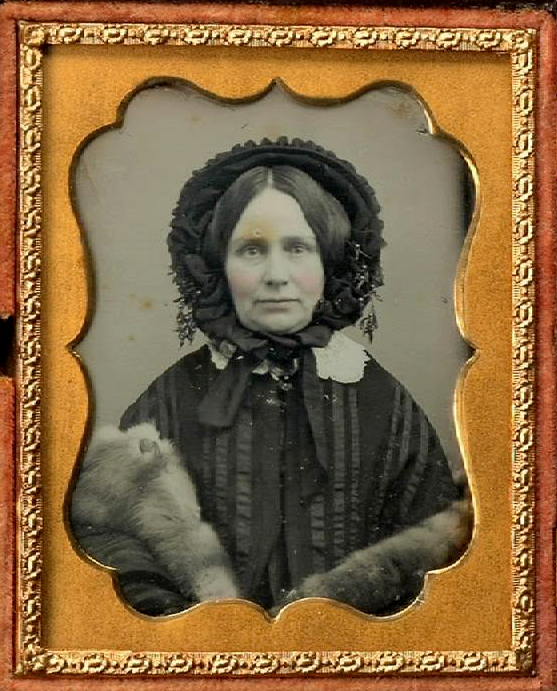

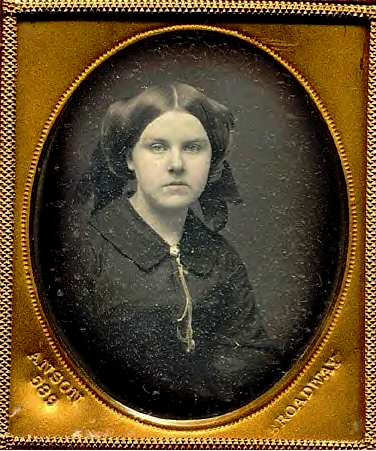

Oops! Fell down another hole. Learn about Field here >. Yep. He’s a primitive painter—but really was gripped by triangles (you will see). The dude had something going on. Ladies and these nutty organza collars? shawls? like our friend Ammi Phillips had (only Phillips was ever so more puritanical). Some of these paintings are templated (red curtain on left, landscape on right) but many are just sock in the likeness and put a nice neutral in the background. However from his portraits, he evolved to doing these nutty landscapes and architectural images which (at least with the Garden of Eden one really makes me think of Pennsylvania’s pride, Edward Hicks who painted around the same time).

The Garden of Eden, 1860.

Interesting insight on the image below:http://www.tfaoi.com/aa/3aa/3aa157.htm

and https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:The_Historical_Monument_of_the_American_Republic_by_Erastus_Salisbury_Field

Historical Monument of the American Republic, 1867–1888

Oil on canvas, 9 feet 3 inches x 13 feet 1 inch, Museum of Fine Arts, The Morgan Wesson Memorial